The history of the modern wristwatch spans almost 150 years and is almost as complex as a Vacheron Constantin Reference 57260.

But the fact is, its origin couldn’t be simpler. As you can imagine, wrist jewellery was commonplace long before the introduction of the portable clock face. Particularly in royal and aristocratic circles where it was considered a marker of wealth and status.

And so it’s believed that the first modern wristwatch was made for the Queen of Naples in 1810, by Abraham-Louis Breguet — the founder of the luxury Swiss watchmaking company of the same name. Some accounts do, however, consider the first contemporary watch as the one made for Countess Koscowicz of Hungary by Patek Phillipe in 1868.

It matters very little who was the first, as before the 20th century, there are many accounts of female members of royalty commissioning so-called ‘bracelet watches’, even including Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Marie Antoinette. What’s more important is when they became known and worn not for novelty and decoration but for their true purpose: timekeeping.

I would rather wear a skirt, than a wristwatch

As watches became synonymous with women and jewellery, for a long time men stuck with the traditional gentleman’s pocket watch. Even going so far as to say, in the words of one 19th century gentleman, “I would rather wear a skirt, than a wristwatch”. It wasn’t until the advent of World War I when the practicality of men having the time on the wrist become strikingly apparent.

Due to the use of the telephone and signal service during warfare, it became paramount to be able to keep accurate time. And so, in the late 19th and early 20th century, the military began to commission watchmakers to create little clocks that could be strapped to their soldier’s wrists. This was a long time coming, as there are even reports of Napoleon being frustrated by constantly having to open his pocket watch during battle.

It’s difficult to pinpoint one exact timepiece as the first modern men’s wristwatch. But one of the earliest examples is from 1880, when watchmaker Girard Perregaux supplied the German Imperial Navy with a batch of wristwatches. It’s reported that one of the officers complained about the inconvenience of operating a pocket watch when timing a bombardment, and even suggested the solution by tying a pocket watch to his wrist.

But it was during WWI which saw the widespread use of the wristwatch and secured its place in the history of the military and men’s jewellery. Some prominent pieces from this time include Cartier’s Tank watch, created in 1917 by the company’s founder, Louis Cartier. The watch was inspired by the square cockpit and lateral tracks of the Renault tanks that appeared on the battlefield, and has since evolved into 41 variations and became one of the most iconic watches ever made.

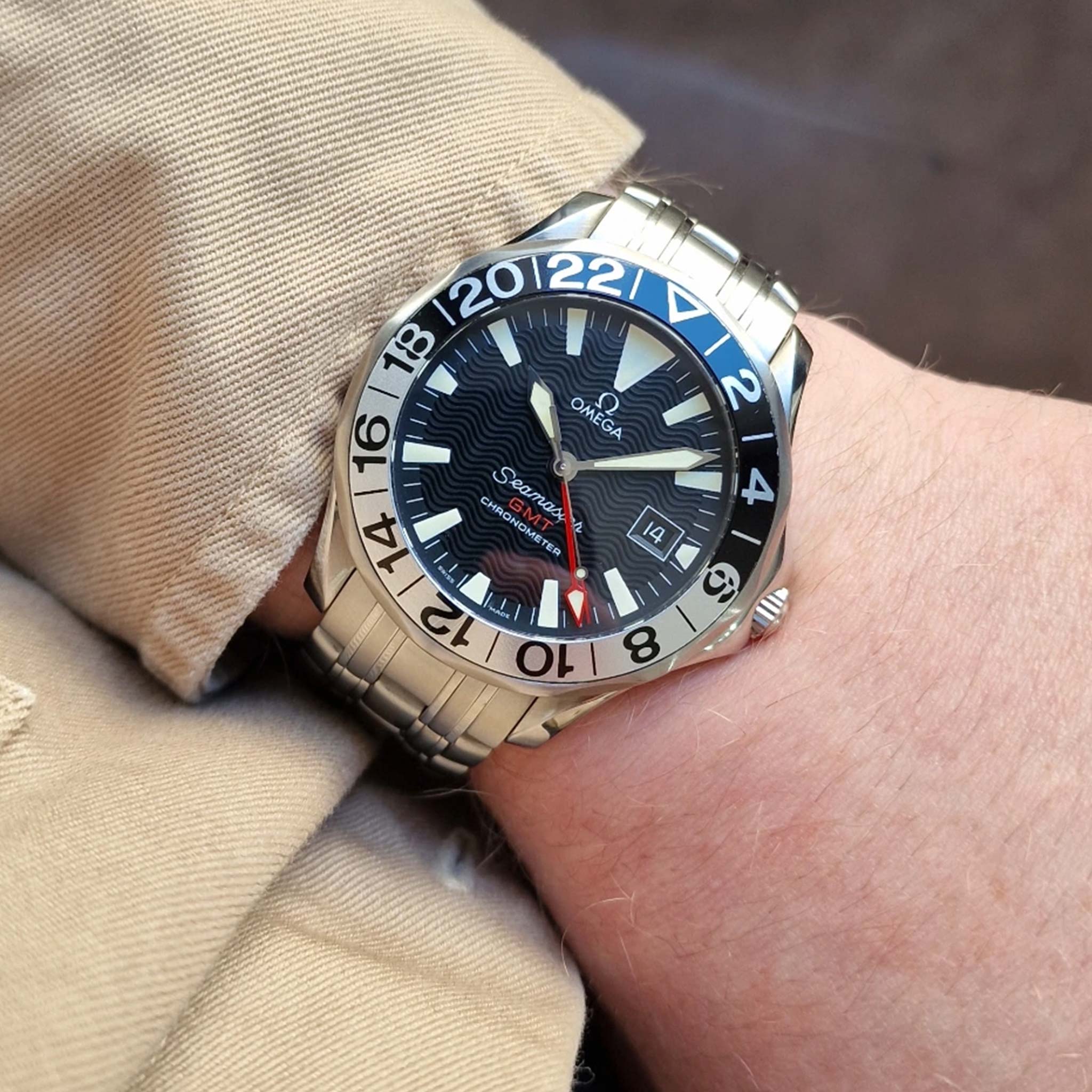

Omega also had a significant role to play in the wristwatch’s proliferation into the mainstream. In 1902, the company displayed an advertisement that showed a wristwatch being worn by a British artillery officer, describing it as “an indispensable item of military equipment.” Watches became so in demand so quickly that in 1916, The New York Times reported that European manufacturers had to work overtime to convert ladies watches into military timepieces.

Continued warfare saw the watch develop into many different styles, the first of which includes the now ubiquitous pilot watch and, of course, the era-defining trench watch. These became the look of the day and were developed further by big manufacturers like Wilsdorf & Davis, which ultimately became Rolex, and The Hamilton Watch Company, an outfit known for its precision pocket watches used to time trains at US railroad stations.

Fast forward to today, and we’ve recently celebrated the 100 year anniversary of the dawn of the modern day timepiece. Some would say wristwatches are now somewhat defunct now thanks to smartphones, but the fact is the industry is experiencing a surge of new interest from younger generations. This is bringing new hope that the art of the craft will not be lost to mass-manufacturing, and that we’re still yet to write many more chapters in the history books of watchmaking.